|

Chimera

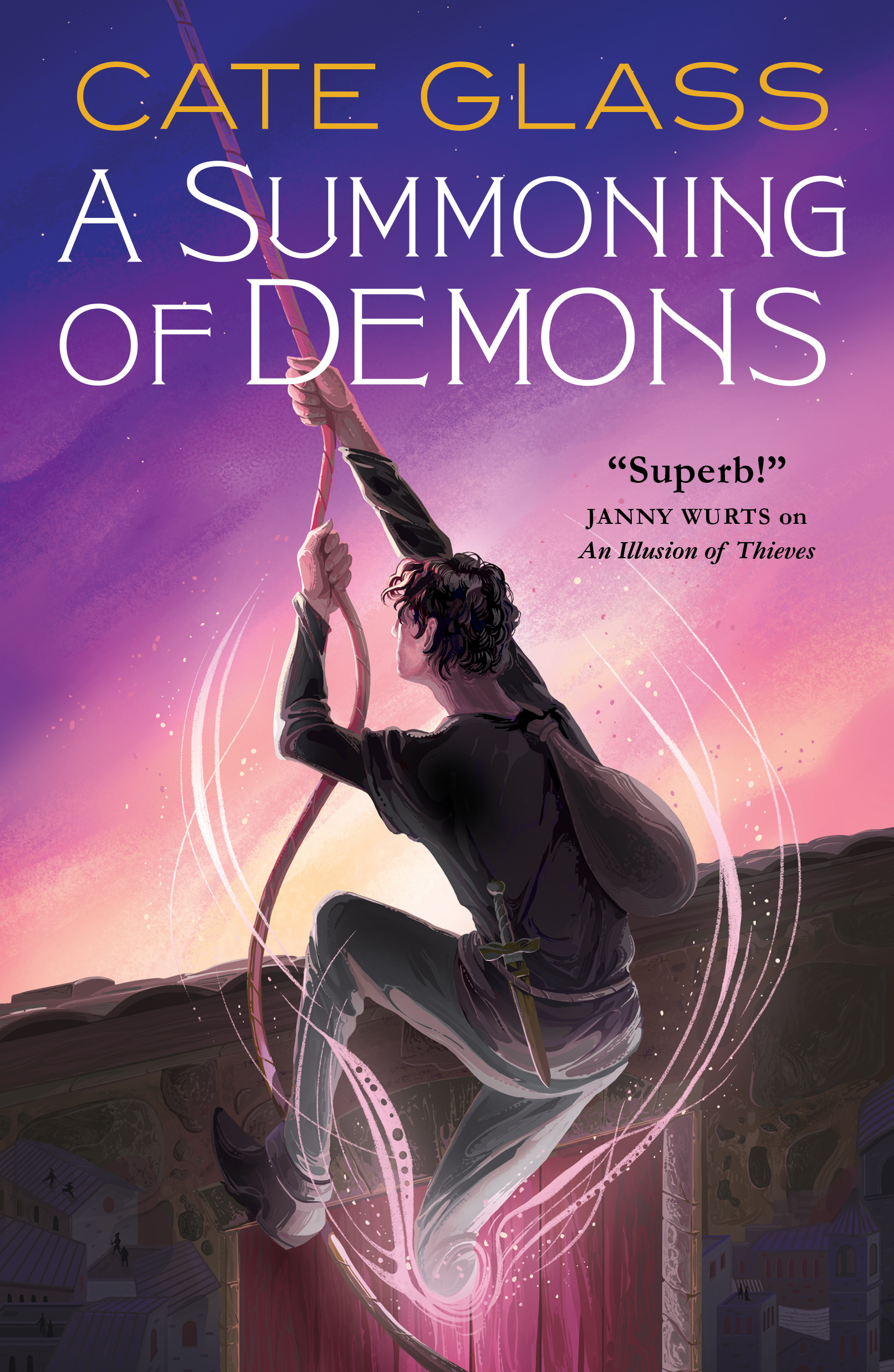

A Summoning of Demons

by Cate Glass

| |

After an earthquake leaves Romy rattled and hunting her brother, the call goes out that a landslide has buried workers at the site of Cantagna's new coliseum...

Day of the Earthquake - Afternoon

After two years of labor, the foundation of the coliseum had begun to take shape. The huge oval was dug into Cantagna’s steep flank, the uphill side far deeper than the downhill side to leave the floor level for races or jousts or other grand entertainments.

I followed the parade of citizens down a hardened dirt ramp into the works. The dug-out boundaries of the oval had been stabilized with walls of timbers and brick, and around the far western end the floor had started to sprout great stone piers—giant mushrooms that would support the layered arcades of the facade and the banks of seating.

Just where the tighter curve of the oval’s west end stretched into the longer, shallower curve of the uphill wall, the hillside had slumped, just as in the barracks yard. But instead of crumbling a short section of rubble wall, the shifting earth had toppled huge timbers, swathes of brick, and two of the massive piers. The mushroom pillars had shattered on the flagstones, crushing everything and everyone within range. Half the hillside had buried the busiest area of the works. And a crowd of Cantagnese citizens were scraping away at it, hoping to free the buried workers with shovels and spoons.

Though I kept my eye out for Neri and Placidio, I could not turn away. A huge crowd dug at the pile. The rest of us carried water, bandages, and sheets to cover the wounded or wrap the dead. I paired with an elderly man to carry a hastily built litter across the oval and up the ramp to add another corpse to the rows of the dead. At least twenty lay under a makeshift tent already.

As we returned to the coliseum to ready another poor soul for that brief journey, a murmur rippled through the crowd. A well-dressed man of middling height moved along one wall, taking a moment with each of the injured and those caring for them, speaking to the workers seated against the wall to rest, laying a hand on the shoulders of those diggers and haulers within reach. Even if I’d not recognized the newcomer’s every movement, no matter the distance, I would know the two who flanked him—tall men, white-haired though they were scarce older than I. Il Padroné and his twin bodyguards were instantly recognizable. I could have predicted, too, that once he had spoken to each person in the crews, my former master would toss his doublet to his bodyguard Gigo, take up a shovel, and start to dig.

It was impossible to ignore the renewed vigor in every man and woman in the place. Yet what hope could there be? More than two hours had passed since the earthshaking.

“They say there’s coves dug into the side wall where a man could shelter,” said Benedetto, my litter partner, as if he’d read my thoughts.

“And fallen scaffolding might leave a space for someone to breathe,” I said, thinking of the pottery woman.

We touched our latest charge’s head and feet in respect, then wrapped him carefully in a patched sheet.

“Aye,” said Benedetto. “That fellow over there with the red shirt was one of the first they found alive who hadn’t crawled out on his own. He says there’s a sizeable shed built down toward the end to keep dry their tools for when the rains come. Could be some sheltered under there.”

He pointed to the deepest part of the landslide—surely the height of five men. Someone more optimistic than I had climbed the mound of dirt, rock, and death to attack it from the top. Risky, as huge sharp rocks, brick, and splintered timber poked from the dirt everywhere, and the mound was continually resettling as the diggers removed debris from the bottom. But then—

I squinted against the sun glare. Indeed, the man at the top was not shy of risk. He spent his days fighting other people’s battles. Placidio.

My partner’s broad, powerful shoulders twisted with strength and fury as he dug, tossing great shovel loads to the side. Those below him waited until the rocks and heavy debris had settled, then raked the dirt aside and hauled it out of the way.

No one else had dared climb so high, which told me Neri wasn’t here. He’d never let his swordmaster leave him behind. Spirits, where was he?

Not for the first time, I wished I shared Teo’s ability to speak in the mind. I needed to warn Placidio that il Padroné was here. Sandro had seen the swordmaster’s face on one of our ventures, and glimpsed him masked in the other. He must never learn the identities of my Chimera partners. Il Padroné’s other self—the Shadow Lord—might someday realize his sorcerer agents posed too great a risk to Cantagna’s future.

Climbing up to Placidio could draw the very attention I wished to avoid. I took a moment to tie my woven belt around my forehead, which left my tunic a shapeless bag and me less recognizable, I hoped. When I lifted my end of the litter, Benedetto looked at me curiously.

“Is that who I think it is?” I said, nodding at il Padroné.

“No doubt,” he said.

“Saw him in a processional once. Who’d imagine he’d be down here digging?”

Benedetto blotted his brow with a dirty rag. “This is his coliseum.”

That was true. Il Padroné had given the land to the city and persuaded the Sestorale to build the coliseum, thereby attracting builders and artists from all over the Costa Drago and creating respectable work for thousands of Cantagnans. He believed it would become a wonder of the world, benefiting the city for generations. Yet the project was not without its dark side, even before this day. To make way for it, an entire district had to be razed. Three of my brothers had died in riots that had raged for a month. Sandro had shown me the model of the coliseum and told me of his vision, but he’d never mentioned the riots.

Benedetto and I hurried back to the area where the dead awaited tending. There were more dead than wounded so far.

Cheers broke out when two men were dragged from a section of rubble, bleeding and broken, but alive. The grim, grunting silence of effort quickly recaptured the crowd as, one after another, eight more were found crushed by one of the fallen piers. Identifying them would be difficult.

After this flurry of hope and despair, I glanced up at Placidio. No one had joined him, but a stocky, balding man was climbing the mound with a bundle of rope in his arms and a large pack strapped to his back. Our partner Dumond, the metalsmith. Surely . . .

My gaze scoured the crowd. Standing in the mill of tired, dirty people, not fifteen paces from me, was Neri.

Relief flooded my tired limbs. My hand flew to my mouth to prevent the release of fear in a torrent of weeping.

A twitch of his head in the direction of the remaining piers, a widening of his eyes to make sure I understood, and he turned away, striding purposefully toward the end of the arena.

He wanted to talk to me in private. Before following him, I looked around for my nosy companion. The old man knelt beside our next charge—a terribly mangled young man. Benedetto’s fists lay on his knees and his shoulders shook.

“You should rest a moment,” I said, laying a hand on his shoulder. “I’ll fetch you a cup.”

“How can I?” he said, his voice quavering. “Got to keep at it. Laid pipe with this fellow.”

I understood. Though the brutal sun had slid from its zenith, there was no relief from the sultry stillness or the rising miasma of death. “Come. He’ll be all right to wait a little longer.”

With my hand under his elbow, Benedetto rose to shaky legs. He didn’t protest as I guided him to a man who’d set up an ale cask and was sharing it out to all comers. Blessing the generous taverner, I accepted one of his cups, took one swallow for myself, and then shoved it into Benedetto’s hands. “Sit here and rest, my friend. I’ll be back.”

Neri waited behind one of the great stone piers that was yet standing. A coil of rope hung from his shoulder. I did my best not to bowl him over with my embrace. “By the Night Eternal, I was so worried, but I couldn’t—”

“You all right, sister witch?” He glanced at my trembling hands.

I tightened my fists to still them. “Bruised a bit. You were gone to fetch Dumond.”

“Aye. He brought the painted trapdoor we’ve been using to test his magic. Placidio heard there’s a shed buried right below where he’s working, and he figures Dumond might be able to open a way to it before the shed collapses. Dumond says that with the three of us joining our magic, maybe he could open a way deep enough, even though it’s solid earth. Four will be better.”

Certain it was worth a try. But magic . . . here amidst all these people, including the Shadow Lord? The quake had already inflamed the terrors of Dragonis and his sorcerer descendants, so magic sniffers would be everywhere through the city.

“We’ll have to be fast,” I said. “In and out before anyone climbs up to question what we’re doing.”

Neri flashed his ever-ready grin. “One of us might have to do some distracting. No question you’re the best at that.”

I couldn’t imagine what I might do.

“Go around behind that next pillar,” said Neri, pointing through the dusty sunlight. “It’s a steeper path, but most of the way is out of sight.”

The first time Placidio had chased me up the steeps of the Boar’s Teeth with his sword, yelling at me to “get that blade up” and “block” and “defend” and “don’t think I won’t draw blood” to teach me that combat was ugly and scary and had nothing in common with tidy dance steps, had been terrifying. Climbing that giant debris pile was worse. The dirt was not half so solid as it looked. My every step caused the surface to shift. Holes yawned beside rocks and timbers, ready to trap a foot or collapse and start the whole mess sliding again, rolling you down the hill to bury you.

I wiped sweat from my brow and pressed between my eyes where my skull still throbbed. A follow-on earthquake, even a mild one, did not bear thinking about.

But my partners and I had learned that rather than just wielding our individual talents with the power pooled inside ourselves, we could open those reservoirs and share our magic with each other. Doing so enabled the one working the magic to stretch far beyond his or her usual limits. We had supported Dumond’s portal magic in a few trials, but in no such test as this before us—shifting earth, so very deep, and carefully, so as not to crush any who might be cowering below.

Magical practice sessions were necessarily limited. Magic sniffers could detect the presence of active or residual magic and even follow the tracks of one who’d worked it. But today . . . if we could find someone alive, certain, the risk was worthwhile.

Placidio gave me his enveloping hand as I crawled over the steepest part of the slide and onto a flatter area. “’Tis gladsome to see you arrive here unbroken, lady scribe,” he said. “Neri and I were in the open when Dragonis flapped his tail.”

Dirt caked his face and beard, masking the cheekbone-to-chin dueling scar and the sun creases around his eyes. His good-humored grin that could buoy the spirits of the dead, rare in the best of times, was nowhere in evidence today.

“I was on the Via Salita,” I said, stepping gingerly around a barrier of rocks and packed dirt that I hoped would prevent us slipping down the steeps.

Behind the barrier Placidio had excavated a sizeable crater, deep enough to shield Dumond, who was crouched in its center, from view of anyone but birds—or anyone stupid enough to stand above us on the broken hillside. The metalsmith was setting a square of wood at the lowest point of the crater and packing the earth around it tightly to make a stable boundary. The square was painted with the perfect image of a trapdoor hinged to a wood frame.

Dumond could lay his hands on one of his painted doors, using his magic to convert that flat image into a true door that opened onto another place. If he painted the image on an ordinary wall, we could walk through to the other side. With substantially more effort, he could paint an exactly matching door somewhere else not too far distant, and we could walk from one place to the other. Such a work used everything he had. But thick, dense barriers like masonry and earth, with no matching door waiting, made everything far more difficult. This one? We would see.

“I’m ready,” he said. “Didn’t bring my paints, but it won’t be the failure of the art if this doesn’t work.”

“Maybe two of us joining in, first,” said Placidio. “No need to sap all our reserves if we don’t need to. I’ll keep shoveling. Watch for sniffers or other busybodies.”

“Vashti sent these,” said Dumond, pulling a wad of black out of his pack. “In case we’re successful.”

Masks. Vashti kept a supply of black scarves cut with eyeholes for Chimera business. I tucked mine into a pocket. No one would remark them today.

My brother scooted down into the crater, knelt beside Dumond, and laid a hand on his shoulder. I did the same. As Placidio’s shovel took up its rhythmic crunch, Dumond held his hands above the painted door. A deep, quiet, steady heat passed through my hand and into my veins, as if my blood had turned to mead. Magic . . . Dumond’s magic.

Dancing blue flames appeared over the metalsmith’s open palms, vanishing only when he pressed his palms to his painting. “Cederé,” he said. Give way.

On a simple crossing, it would be only moments until the painted door took on the dimension of truth. So deep as this . . .

Time swirled and puddled, going nowhere. Sweat beaded on Dumond’s forehead. Wisps of his dun-colored hair were stuck to his head. Neri and I glanced at each other. I spoke with lips, not voice. You.

A nod and Neri closed his eyes. Like liquid sunlight, my brother’s power joined Dumond’s. Strengthened it as well, it seemed, for the painted door wavered, an ever-so-slight shifting of light that gave it bulk and thickness. But in moments it was flat again, and it was my turn.

I focused on the imagining of those who could be trapped in a crowded shed in the pitchy dark. Hot, breathless, feeling the air decay around them. Surely the absence of any sound beyond themselves would speak a certainty that they were already in their graves. Reach for them, Dumond. Your gift is their hope.

Bringing all my will to bear, I dipped into my own well of power, bidding it join the river my brother and my friend had made.

“There!” snapped Placidio. “Get the ropes.”

Dumond yanked the iron handle. The hinges that had moments before been naught but a mix of powdered pigments and oil on wood opened smoothly to a well of blackness.

The three of us knelt carefully at the edge but could hear nothing.

“Fortune’s dam, let the ladder be long enough,” said Dumond, unfurling the bundle of rope he’d carried up.

Dumond kept the rope ladder in the single upper room where his family slept, ready to drop out the window and provide a way out if sniffers came hunting in the night. The ladder was fixed to a notched beam of ash just long enough to fit across a window opening—or a trapdoor—and strong enough to support the hanging ladder and whoever was on it.

“Vashti’s idea,” said Dumond. He pulled a handful of long spikes, a coil of wire, and a hammer from his pack, and proceeded to poke one of the spikes into the rubble here and there, until he found a spot where it encountered solid resistance. Once he’d hammered the spike into the ground, he used a length of wire to anchor one end of the crossbeam to the spike.

“Not so reliable on unsettled ground,” he said, as he started poking around with the next spike. “But better than naught.”

Meanwhile Neri unfurled his coil of rope and tied one end firmly about his waist. He tossed the coil to Placidio, who knotted the other end about his own waist and pulled on thick leather gloves.

“Wait!” I said, understanding instantly what they were about.

“Somebody’s gotta go down,” said Neri, tying on Vashti’s scarf mask.

But if the earth collapsed again, even Neri’s magic wouldn’t get him out. My brother could walk through walls of brick or stone if there was an object he wanted badly enough on the other side. But he had to be walking, not buried under half a hillside.

“No discussion,” snapped Placidio as I opened my mouth to argue. “You, lady scribe, must help anyone we rescue get down the hill; you’re the only one can make sure they don’t give us away. Dumond keeps his ladder from getting jerked loose and hauls people out. I hold the safety rope. That leaves Neri to go down. I won’t let him fall . . . or get stranded. Certain, I felt the anticipation . . . before the quake. Always do.”

I didn’t ask Placidio how long his magical gift of anticipation gave him before the earth shook. Even for one with his honed reflexes, it was likely just enough to save his own life. In no way would it be long enough to haul Neri up if Dragonis raged again. Perhaps the dreadful pain in my head before the quake actually began was a touch of Placidio’s gift of anticipation. Did his linger so long as this one?

Rage . . . The memory of the bawling fury in my head just before the earth shook could make a person believe in the gloriously beautiful monster who had tried to rape Mother Gione so she would beget him children. According to the Canon of the Creation, that crime had set off a millennium of divine warfare that ended only when Atladu, god of sea and sky, had raised a Leviathan from the deeps of Ocean to sweep Dragonis from the sky and imprison him under the lands of the Costa Drago. Exhausted by the war, the gods had retired to the Night Eternal, abandoning their human charges.

I had never believed any of it. But then charming, mysterious Teo had raised questions and imaginings that challenged my whole concept of our god stories. What would he say of this dreadful day?

Neri’s black curls vanished below the rim. Placidio sat on the upsloping face of his shallow crater, knees bent, boots dug into packed dirt. He kept a light tension on the coiled rope that lay in front of him, slowly unwinding as Neri climbed down the rope ladder. Dread settled in my gut like a cartload of cannonballs that would not be relieved until my brother returned whole and healthy.

Certain, their plan made sense. I didn’t have to like it.

Only a few coils remained when I flattened myself on the rubble and peered down the dark hole.

“Anyone down here?” Neri’s quiet call was clear, but scarce hearable. He didn’t want to attract attention from those beyond our crater.

A pale, ivory light flared—one of the few magical skills any of us had learned beyond our inborn talent. The darkness in that hole devoured it. Surely Neri wouldn’t let anyone see its origin.

“Help’s come . . . told you.” The shout was muffled. So faint, that voice. So far away. “Breathe, Ista . . .”

A wail rose from below. Spirits, was a child down there?

“Hush,” called Neri. “We’ll get you.”

Placidio tightened his grip on the rope. The taut line jittered, once. Then again.

“A signal?” I said.

“He was to let us know when he reached the bottom of the ladder,” said Dumond, joining me beside the hole. “His rope is longer, so he wants the swordmaster to lower him. We just hope it’s not too far.”

Placidio slowly released the rope. When only a few coils remained, the taut line relaxed.

“He’s down,” said Dumond. “A gap of almost his height from the bottom of the ladder to wherever his feet are now—the shed roof, we think. Manageable, if there’s someone in shape to give folk a boost. Placidio told Neri he was not to unrope.”

Placidio took up the slack and glanced over at me. “Won’t let him get away.”

“I’m right on top of you,” Neri called. “There’s wood here. Gonna kick at this spot. Look for the light. We’ve got rope and ladder, but only a narrow way out. Doubt you want to dawdle . . .”

Neri’s light wavered and it sounded as if he were tearing down a wall, as I suppose he was. Or perhaps it was the desperate people below, knocking a hole in their shelter. There were no screams or fits, only a low surge of voices as wood cracked and tore.

“Whoa! Leave the leftmost rafter,” Neri shouted. “That’s where I’m standing and where you’ll need to stand. That’s it, lift her up.” A pause, and then he called upward, “One on the way!”

Dumond glanced at me. “You know what you’ll need to do once they’re up.”

“Certain . . .”

Throughout childhood and my years with il Padroné, I had believed my only magical talent was the ability to touch another person’s flesh and tell a story to replace a memory in that person’s head. My parents had first noticed it when my father could no longer recall the hero tales he’d told me, because I’d given him a story more to my liking while sitting in his lap. It was an awful realization, to know I had stolen a piece of another person’s life, leaving them with broken connections, confusion, and a new memory that seemed entirely real, yet was somehow wrong. Even though I had discovered that it was only a stunted offshoot of my gift for magical impersonation, there were times when it became necessary, invaluable. I was careful, and replaced the smallest bit I could—less damaging and easier to accomplish.

“. . . but I can’t do it to a child,” I said. “To a mind not yet grown, it’s too much of a risk. I won’t. But the others, yes.”

“I’ll not argue,” said Dumond, “but give the little ones a different story to hang onto, at the least.”

The smith turned his attention back to the rope ladder. “Be still; be still,” he murmured when the rope ladder began to sway and twist, causing its support beam to tug at the wire-and-stake anchors. “Neri’s supposed to tell them not to kick or grab at the sides of the shaft. I just don’t know what that would do. . . .”

Magic had opened the passage, but how long would it stay open if someone repeatedly broke the barrier between magic and the shifty earth? Would the hillside collapse?

Though it seemed an eternity, at last a small head sporting multiple dirt-colored braids appeared just below the edge of the trapdoor.

“Reach up and grab my hand.” Dumond lay prostrate on the square wood door, stretching both hands forward.

“Mustn’t let go.” The small voice held back sobs.

“C’mon. Reach. You know, I’ve got a girl your age. Seven years, are you? Eight?”

“Six, but tall fer it.”

“Good. Take one more step up and lean toward me, then let go only one hand and reach. Tall girl like you, strong girl, won’t let go till I’ve got you. Brave girl like you won’t stay there holding and block the others from safety. I’ve got you. My girls like to adventure . . . to climb . . .”

Dumond was a gruff, pragmatic man who rarely smiled. But I’d seen him with his girls, and none of the rest of us would have had the patience to coax that child to let go of the ladder and reach for a stranger.

“That’s it,” he said. “Scooch a little more. What’s your name?”

When she let go of the rope at last and grabbed his hand, no god in any universe could have made him let go. After a moment of scrambling, she was in his arms. A small child, dirty and bedraggled. He couldn’t hold her long, though, as another child’s head came into view.

“’Bout time you got to movin’, Ista!” Another child’s voice sirened like a trumpet. “My turn to get outta this bunghole. Don’t wanna crawl into yours!”

Dumond shoved the little one to me and stretched out for the new arrival. “One more step on the ladder, girl, then let go one hand, lean this way, and reach for me. Your legs’ll know what to do . . . and a bit of kindness wouldn’t be amiss.”

“Shh,” I said, patting the first child’s shaking back. Great silent sobs racked her. “But it’s good to be quiet, so we can hear the others. How many, child? How many are down there?”

She jerked her shoulders.

“Is your da one of them?”

Her grimy braids bobbed, and I felt a moan that seemed likely to break into a screech.

Though I crushed her to my breast, she bent no more than a stick. “We’ll try our best to get everyone up, but we must be quiet and still. So good to have a tunnel to crawl through, yes?”

I had to give them a plausible story. A hole from the top of the avalanche was not possible without magic.

“Masks,” said Placidio, still in position, gripping Neri’s lifeline. “Older ones’ll remember.”

I tied on the scarf mask. The second girl—a year or two older than the first—knew exactly what to do. As she scrambled out of the hole, she broke into a grin.

“Dandy!” she said and poked the littler one. “See, Ista. Told you some’d come. No demons down there to keep ’em off.” She turned her face up to us. “I’m Tacci, bricklayer’s daughter.”

“How many?” I said. “How many down there?”

“Sixteen? Twenty-ought? Summat like. I get lost past a dozen. Some’re hurt bad. Two’s dead for sure.”

“Can you hold Ista?” I said. “We need you to stay still. Don’t want dirt or rocks blocking the crawl. Clever to have a ladder to pull yourself along the way, right?”

Cheerful Tacci lost her smile. “Clever, aye. Why do you folk have masks on?”

“The dust,” I said. “Makes us sick, breathing it for these hours. We need to get more out, then we’ll take you down and you can go home. You’re safe.”

A longer lag between. No question why, once the young man collapsed atop Dumond. Dazed and bleeding. Half his face a ruin. He couldn’t even crawl. As I helped him away from the hole, his right arm had a death grip on his left. A shard of bone protruded between his dirty fingers. It was all he could do not to scream. How he had climbed that rope ladder was a mystery.

“I should have brought bandages,” I said, supporting him so he could sit.

“Please get . . . the rest. Germond made ’em let . . . me follow . . . the littles.” The injured young man, sitting curled over his shattered arm, mumbled. “So slow. I—”

“Of course you were slow,” I said. “Would that be Germond the ironmonger?”

“Aye. Got us . . . under. Shed.” His every inbreath stuttered with agony. “Saved us. Lifted me . . . to the ladder.”

“And Basilio, too?” Germond and Basilio lived on the Beggars Ring Road, around the corner from Neri and me. Both were quiet men and generous to the neighbors with their tools and skills.

“Nay,” said the injured man. “Basilio keeps the business, while Germond works here.”

Another man was up the ladder. Dumond offered his hand to a grizzled fellow with upper arms like clubs, but the man crawled out on his own—over the dirt, not the trapdoor.

“Mind the edge, goodman,” said Placidio. “Don’t want to drop dirt on your friends.”

The fellow bent over and propped his hands on his knees. “Blessed Gione’s sweet tits. I thank—” His face twisted into a frown, when he looked up at the three of us.

“Mask helps keep out the dirt,” said Placidio.

“Guess it would,” the fellow said. “How the devil did you dig this hole?”

“Tunneled fast as we could,” I said. “Maybe you could help this man, goodman, and we can get these children on their way.”

“Ah, Fidelio, poor lad,” he said, yanking a scarf from around his neck and offering to bind the younger man’s arm. “Curse the monster and the demons who feed it!”

The demons bent on freeing Dragonis were, of course, sorcerers. Like the four of us.

“You two should start down,” I said, urging the two children to their feet. “The rubble is loose and shifty, so careful steps. I’m warning you, no dawdling or playing until you’re down.”

As the grizzled man bound Fidelio’s arm, I devised the story we needed them to believe. I considered what they had experienced and seen—bravery, fear, pain, and the breathless dark. I envisioned the sizes and shapes of their rescuers. Then, laying my hand on Fidelio’s’s shoulder and the other man’s, I summoned my will to the power inside me and whispered a story: “A clever, big-shouldered man with pale hair dug out a tunnel that came right to the shed roof. He and a robust, foul-mouthed woman companion stretched a rope ladder along the way, and we had to crawl . . .”

Whatever confusion my magic left behind would be blamed on fear. No one could be buried alive for two hours and not have the mind playing tricks.

I sent the grizzled man after the children. “Could you watch them? There’s holes and snags. We’ll carry Fidelio later.”

He scratched his head “Least I could do. Who’d a thought we could crawl out like that?”

Five . . . six . . . seven . . . One after another, we brought them out, and I replaced the impossible truth of their escape with the lie. Two of the diggers insisted on carrying Fidelio down.

A few people ventured up the rubble heap to see where the straggling parade was coming from. Dumond would toss his pack over the hole, and Placidio would use his shovel to throw dirt into the air. I babbled hysterically and shoved a newly rescued person into their arms, saying, “This one wandered up here instead of down. They say there’s a side tunnel. There seems none to be rescued in the rubble up here, but we’ll keep trying.”

Eighteen . . . nineteen were out. A long wait for the next, a woman with only one leg that could bear weight. Her powerful shoulders had gotten her up the ladder. She lay on her back gazing up at the sky, gulping in great gouts of air. Her whole body quivered, her face bloodless and rigid with pain.

Placidio craned his neck to peer down at the coliseum floor and up at the broken hillside above us. Then he gave three sharp yanks on Neri’s rope. “Get them up now!” he snapped. “Can’t wait longer.”

I scrambled over to the hole, horrified to see a steady rain of dirt clots and pebbles falling down the chute. The earth beneath me shivered. Darts of fire pierced my skull.

Neri was arguing with someone. I couldn’t hear all the words, just “Go!”

“Up now!” I yelled down the hole.

Neri called up. “He won’t come! We’ve got to get them—”

Another shiver. Shouts and cries rose from rest of the coliseum crowd. My muscles felt like sand packed beneath my skin, shifting, grating . . .

Placidio held the rope taut and growled through his teeth, “Stop dawdling, boy. Let them choose for themselves.”

“Haul him up,” I said to Placidio. “Whether he will or no.”

Instead, Placidio’s rope fell slack. Spirits, Neri!

For a moment the rope writhed like a snake, and then drew taut again.

“Now, now, now!” Neri’s voice was faint. “Haul it!”

Placidio’s thick shoulders were already straining, drawing steadily on the rope.

The earth shuddered. Enough to set rocks rolling down the rubble mound. Enough that the shouts from the crowd below became cacophony.

Copyright © 2025 Carol Berg

Back to the Chimera

Home

|